Tuesday, January 31, 2006

Monday, January 30, 2006

Sunday, January 29, 2006

Brick Devereaux

Somebody recently asked me if I had a photo of Brick Deverereaux. I looked quickly through some book, and couldn't find any. Yesterday, looking for something else, I came across this photo. So here it is, whoever wrote me.

Below are Devereaux's stops in his long playing career.

William "Brick" Devereaux--3b, ss, p (aka "Bill" & "Red Dog")

Born: August 31, 1871 Oakland, CA

Died: January 27, 1958 Oakland, CA

1892 Oakland/Oakland Piedmonts/Oakland Morans (Central Cal)

1898 Santa Cruz (Pacific States)

1898 Santa Cruz (PCL)

1899 Santa Cruz (Cal)

1900 Sacramento (Cal)

1901 Sacramento (Cal)

1902 Oakland (Cal)

1903 Oakland (PCL)

1904 Oakland (PCL)

1905 Oakland (PCL)

1906 Oakland (PCL)

1907 Oakland (PCL)

1908 Santa Cruz (Cal St)

1909 Vernon (PCL)

1909 Santa Cruz/Sacramento (Cal St)

1910 Bakersfield (SJV)

1913 Vallejo/Watsonville (Cal St)

Saturday, January 28, 2006

The Corrected Death Information on Jay Hughes

Alan supplied this information just before the Christmas holidays, but am only getting to it now. This is also a cautionary tale about using one source, which I apparently fell victim to myself.

I just wanted to clarify some info about Jay Hughes. I have the original news account from the Sacramento Bee about his death. He died from a fall off the Sutterville Road over-cross trestle in Sacramento on the "Walnut Grove Line.” This line used to run from downtown Sacramento through Sutterville (now the Land Park neighborhood in the south of Sacramento) to Walnut Grove. The tracks are still there, but the train no longer runs, and the trestle was removed in the early 1960s. I used to walk on— and play on— the trestle on my way to school at a school that backs up to the tracks and was next to the trestle. I grew up within blocks of where he died.

The article also states that his baseball career ended in 1907 due to a back injury.

Through my own research, I found that he was a "driver" (probably of horses) in 1908. From 1909 thru 1911 he worked for the city streets department. In 1912 and 1913 he was a gardener at the state capitol. At the time of his death he lived on a ranch off Sutterville Road and was the caretaker for the Sutterville baseball field.

I have heard second hand from the family that after this he became a bartender and developed a drinking problem which, in all likelihood, contributed to his fall from the trestle.

I appreciate the opportunity to share info about Hughes as he is one of my favorite local players.

Alan O’Connor

Usually the reporters for the A. P. were the best around (way back when that is). When I published the first news account, I never gave it any thought that the A. P. could have gotten it that wrong. Walnut Grove is not Sacramento, and the Walnut Grove Line is not the same as the town of Walnut Grove.

After Alan sent me a copy of the Bee account, he went and photocopied the Union-Republican account. Above I'm posting all three accounts of Jay ughes death, and they point out the reason for checking more than one source, if you can.

A Word About Historical Statistics

A Word About Historical Statistics

FYI...

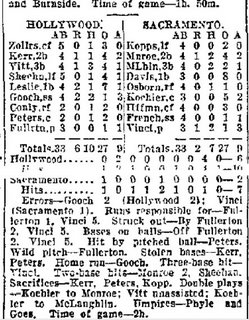

Attached is a box score of a game between Hollywood and Sacramento, played on 4/28/1926. You will note that the Stars' Charley Gooch hit a homer in this game. However, according to the Old Time Player Database and your Cyclopedia, he is not credited with any homers in 1926.

Isi Baly

Isi seems to chide me about missing the Gooch home run. But if you check the guides, Charley Gooch is listed with “0” home runs in the guide. I did not go back and recompile every Coast League season from 1903 through 1957. As I explained to Isi,, I correct the mistakes as I come by them, just like the editors of the encyclopedias do. I did, however, recompile season batting records 1903-1906, and seasonal pitching records 1903-1910. I also attempted to compiled records for all the players who did not appear in the guides— for the most part “less-thans”— though I probably missed a few over the1906-1937 period, because the only way to really make sure that you have everybody is to compile the complete season from box scores. Obviously, something that would be a “life’s work.” I also compiled individual pitching stats for every season that didn’t exist; e. g., saves.

For 1903, I found one player, Deacon Van Buren (who was listed many places as the league leader in batting), whose BA dropped from .360 to .319. Generally, most players were close to what the guides had, though far enough off to require a redoing of the stats.

What do I attribute the discrepancies to? I attribute the differences to sloppy record keeping. And pitching, over the years, was much worse than batting.

Did it get better over time? It tended to fluctuate: 1905, for instance, I found— after a couple of months’ work— to be almost identical to the official averages. Now that was a big disappointment. Though pitching records were very incomplete, so it wasn’t all wasted effort.

Stats for 1918 turned out to be spot on, though no pitching averages were published, so my work was not in vain.

The stats for 1930 were so bad that the Coast League brought in Irving Howe (who would later create Howe News Bureau)to do the 1931 stats for the league. (I plan on redoing the stats for 1930 whenever I get a chance. They must be atrocious for the PCL— never the league to care about the historical record— to declare them so.)

Willie Runquist started recompiling stats from 1938 on, and to give you some idea of what he found, I’ll quote from his 1938 Pacific Coast League Almanac: “Finally we would note that most of the differences may be so small as to be unimportant.”

But just as we begin to feel confident with the official averages in the league, they get worse in 1939: “The discrepancies are considerably larger than they were in 1938…”

What does this all mean? It means that for the Coast League statistics were generate in-house, and the quality depended on the person compiling them. And, generally, pitching records were worse than batting records. Therefore, recompiling pitching stats should be the priority, though several seasons, like 1930, should be done top to bottom.

Friday, January 27, 2006

On Minor League Stats & Today's Two Published Baseball Guides

Hey Carlos,

It is quite interesting to find the stats that baseball holds as its own, all of the stats that are in any baseball book. I mean these stats are what baseball is all about basically, that’s what makes baseball “baseball” in my opinion.

I look at the Baseball America books, and those I trust because BA actually covers the minors during the season. Yes, sometimes I find mistakes, but not too often. I also look through the Sporting News Baseball Guides and always find a lot of mistakes.

Yes, in the BA stuff they don’t put the stats in for every player, you have to play in like 10 games or something (I don’t remember for sure) and the Guide supposedly has everyone that played for the year.

That is why in the database I’m trying to put together the stats through the box scores as those I know I can trust. and if I find a mistake— as unfortunately I have found a lot in recent years— there's usually someone around who went to that game or has some knowledge of what happened in the game.

Thanks for you time and keep it up Carlos.

David Malamut

David has chose the thankless task of trying to find box scores for every minor league game played in the last few seasons, with the hope of being able to correct the errors and lack of completeness found in the guides today.

This evening— because I missed posting yesterday— I will post a box score from the 1920s that one of our readers found, and which proves the guides to be in error. Why am I not surprised?

The problem with today’s minor league records is that a number of minor league cities have chosen no to publish box score for their teams. Additionally, scorers now do their scoring online, and there is never a paper record. And the most egregious is that most people attending minor league games don’t score the game. Don’t know how to score a game. Couldn’t care less.

Tomorrow I will publish an update and correction on Jay Hughes by researcher and Hughes expert Alan O’Connor. It will be a cautionary tale, a trap in which even I get snared from time to time, including this time.

Wednesday, January 25, 2006

An Update from Robert Schultz on TSN Stats Fiasco

Carlos:I have been following with great interest the debate over the flawed stats in the 2005 TSN Guide. In the age of the availability of computerized stats, the TSN has no excuse for omitting as much information as they did in the guide. I checked all players on the New Britain roster of the Eastern League and found that any player not on the roster at the end of the season did not have his stats included in the guide. The following players were either promoted, demoted, traded or released before the end of the season. Elvis Corporan, B.J. Garbe, Jason Kubel, Kala Kuhaulau, Billy Muñoz, Matt Scanlon, Kevin West, Scott Baker, J.D. Durbin, Jannio Gutierrez, Rick Helling, Beau Kemp, Pat Neshek and Jason Richardson. None of them appear in the guide. This is probably the case for all missing player stats. The interesting thing with Jason Kubel is that the TSN Register has his New Britain stats. Baseball America Almanac is mostly complete. The problem is they do not have pitchers batting stats and do not have stats for hit batsmen, sacrifice hits and sacrifice flies.

I would sure like to see a corrected guide published by someone (possibly SABR) in the near future.Thanks for your timeRobert Schulz— SABR member and minor league fanP.S. I enjoy visiting your minor league blog site

That’s all that I asked for, but TSN chose to stonewall the whole matter, and they hope it goes away. The problem researchers will have in the future is that it will be hard to put together a full set of box scores. And the more the world goes digital, the more likely box scores will just be deleted at the end of the season. The more we go digital, the less important saving things for history will become.

Tuesday, January 24, 2006

From The Sporting News, March 28, 1903

Why don’t they just stick to planting palm trees in the outfield?

The grounds of the Baltimore Baseball club will be the finest in the country [where have I heard that before?] One of groundskeeper Murphy’s pet schemes has been to fix up a diamond with the four aces, which, besides being a very good hand to hold, has other advantages. Thousands of sods have been applied and yesterday Murphy’s idea was beginning to show for itself. The ace of diamonds is, of course, the inside playing field. The ace of clubs has been laid at the pitcher’s box and the ace of spades at the batter’s position. The handle of the spade is directly behind the batter, thus giving the pitcher an additional mark at which to pitch. [Just what is needed in the deadball era, only giving further evidence of how hard it is to kill baseball, though they haven’t given up.] The ace of hearts is formed by the outer lines of the infield, and the curved indentation is directly back of the second bag, giving the catcher a fine mark at which to throw. It can be readily appreciated [or not] that Murphy’s scheme has practical advantage in addition to being unique [for sure] and pleasing appearance [debatable]. — Baltimore News.

Monday, January 23, 2006

From the December PCL Potpourri

In the lead article, Over 40 and Loving It, Dick Beverage gives an overview of the best over-40 year old players in Coast League History based on the research of Terry O'Neil. The conclusion they drew is that Earl Sheely was the best over-40 postion player. The summary of his 40-career is above.

The PCL Potpourri is 6-times a year newsletter published by the PCL Historical Society, 420 Robinson Circle, Placentia, CA 92870. Cost is $15.00 per year.

Sunday, January 22, 2006

More Bad News for the Sporting News

I spoke today to a researcher who doesn’t want to be identified at the present time, but told me that he made a comparison between Baseball America’s 2005 Almanac stats and TSN 2005 Baseball Guide stats, and found that the BA Almanac had batting and pitching stats for players that did not appear TSN BB Guide. Apparently, it looks like TSN left off the bottom of the page; i. e., there were breaks in the alphabetical list of players. (I have not, as yet, checked this out, but will do some looking this week.)

Steve Gietschier wrote the following in response to my call for posting corrected stats on line:

Carlos suggests that TSN post corrected 2004 stats on our website, but as Greg notes, those stats don't exist.

I accepted Steve Gietschier’s statement that those stats do not exist, but apparently Steve is not well-informed as to the culpability of TSN, so, therefore, I will renew my request, as the stats published in the TSN BB Guide do exist, and never made it into their publication.

Saturday, January 21, 2006

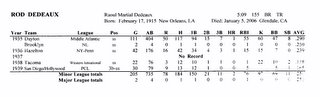

Some Help for those Wanting to Print Out Career Records, Etc.

Because all the career records, order forms, etc., are photo (jpegs) there is an alternative way of getting them into paper form.

First, click on the record, which will expand it to full screen.

Then, once it's up there, use the right mouse button and click. That should give you a menus of options.

Choose "Save image as" and click.

That should let you down load it to your computer.

From there you can find it and print it out just like any photo. Or you could even insert it into Microsoft Word document, and then print it out in Word.

That should take care of your printing problems.

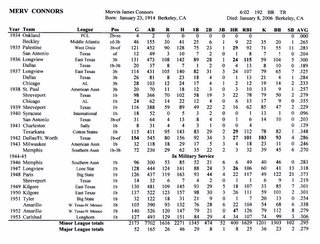

Coast Leaguer & MInor League Star Merv Connors Dies

Doug McWilliams learned of the death of Merv Connors, and he passed this SF Chron clip on, via Mark Macrae:

Connors died in Berkeley, California on January 8, 2006 at the age of 91.His father was Fire Chief for the city of Berkeley in the 1930's. After graduating from Berkeley High School, Connors would have a two decade career in baseball , mostly in the lower minors. He was a paratrooper in WW 2, going into France on "D-Day" with the 517th Para-infantry. He fought at the "Battle of the Bulge" and in Africa in the mid 40's. Exited the military as a Seargent. He spent the balance of his life as a delivery truck driver in the East Bay region of Northern California. He credits his long life to his adult habits of drinking beer, smoking cigarettes and chewing tobacco.

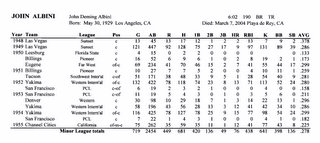

His minor league career was good enough to get him into the first volumn of Minor League Stars, from which I took most of the stats, adding BB & K data from the guides. His 400 home runs hit in the minors is still near the top of the list of all-time career home runs.

Friday, January 20, 2006

John Benisch with More on TSN/Minor League Baseball Stats Fiasco

Carlos,

TSN did not publish identical stats for players in its Guide and Register. Example: Jeff Keppinger [Eastern League]— 123/362 in Register and 125/370 in Guide along with differences in ther entries. The Guide lists Keppinger 1st @ .338 and J. Castellano 2nd @ .340 [among qualifiers]. TSN should at least point out the document with the more accurate data to aid historians.

Also, Cal Pickering [soon to play in Korea] is omitted from the batter listing in the Guide but has a 2004 batting line for his PCL performance in the Register. I'm sure there are many more examples of contradictions and omissions.

As a minimum, TSN should provide access [via Web or print] to the minor league individual batting lines that were left out of the 2005 Guide.

John

I talked to a retired baseball executive, and he told me that everybody in O. B. knows the extent of the problem, but they are into the “stonewall” mode, and will not even consider helping historians in trying to correct the record. This executive went on to tell me that he believed it to be the worst minor league scandal in the last 40 years. They are all in full CYA mode, he concluded.

Well, along with the “steroid scandal”— here’s another one that the MSM completely missed— I mean, chose not to report on. Sorry.

As for myself, I will attempt to compile stats for two leagues from newspaper box scores, the PCL and the California League.

Thursday, January 19, 2006

Mr. X Passed Away in Arizona

Last week Dick Beverage told me of the death of Xavier Rescigno, and the date of death, but didn't know where he had died, though he thought Arizona. Bill Swank passed on the place of death. I had to spend a several days to put this record, as I had to compile several season that didn't appear in guides by compiling the stats from box scores. It is, without doubt, the most complete career record of his ever published.

His 154 wins is of note, as is his four solid Coast Leagues seasons.

Wednesday, January 18, 2006

A Bauer-Pastier Exchange

John Pastier wrote:

Over their heads? [I had written him that his post might go over the heads of some.]I thought it was between the letters and the knees.It's amazing that no one considered the implications of what Geitschier was saying— that TSN doesn't have the resources to turn out an accurate publication, but that they will fake it anyway.—JP

Bauer answers:

Your absolutely right. And his comment that the leagues put the stats on their websites, and "does that mean they don't give a damn, either?" That one was too easy. I just had restrain myself from hitting it out of the park— if they published the stats knowing that they were bogus, then of course they "didn't give a flying deleted!"

[Personal note deleted.]

Carlos

Tuesday, January 17, 2006

A Comment By John Pastier

Renowned ballpark researcher John Pastier set me a copy of his post sent to SABR-L, which follows:

Steve Gietschier wrote:

. . . we surely do give a damn. Anyone who doubts this is invited to

come to our offices any day between the end of the baseball season and

the tenth of January and watch an understaffed group of editors work on

our annual baseball books while simultaneously performing all the other

tasks we are called upon to do. No tears, please, it's just the truth. We

do the best we can in the time we have allowed, and the data we were

preparing after the 2004 season were severely flawed.

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

I fully sympathize. The mainstream journalistic world has been severely

eviscerated by corporate bottom-line-itis.

Good people labor under absurd conditions because corporate suits expect

ever-larger profit margins in a declining and inherently labor-intensive

business.

But average consumers aren't aware of the conditions that Steve

describes. They assume that a TSN imprimatur guarantees the sort of

truth and accuracy that one might expect from a bible.

I suppose that corporate management has the right to pursue any profit

target it wants, but shouldn't there be some truth in packaging for the

benefit ofthe consumer? Maybe these books should carry a prominent

disclaimer on the front and back covers, and on the title page, saying:

"This book is the product of an understaffed group of editors who work on

TSN's annual baseball books while simultaneously performing all the other

tasks they are normally called upon to do. They do the best they can in

the short time allowed, and the data in this book may therefore be

severely flawed.

Buy at your own risk. -- The Management."

-- John Pastier

I wonder how many got the humor of the above?

The Hornet's Nest

The Society of American Baseball Research (SABR) is sort of like a church, and if one happens to made even the most fact-filled criticism of anything remotely related to another SABR member, the walls come down on you. Like the Church in the Middle Ages, SABR would prefer to pretend that the world is still flat, and if it isn’t one should keep their mouth closed. Lyle Spatz posted the following: “As chairman of SABR's Baseball Records Committee, I can attest to the fact that Steve Gietschier does indeed give a damn. Since taking over the compilation and editing of the TSN Record Book a few years ago, Steve has worked very hard to streamline the Record Book categories and improve their accuracy. He is extremely cooperative, open to suggestions, and willing to make necessary changes.”

The only problem with this is that Steve Gietschier is not listed as editor of the 2005 Guide, and that it doesn’t get to the problem of the 2004 minor league statistics. What I find confusing is that on one had they, those at TSN, state that they didn’t have anything to do with the stats that were supplied to them. That, in short, they published what they got. Then they claimed that they are overworked, and that they really do care. I don’t know that that adds anything to the dialogue.

Did they really think that nobody would notice? Or that they would keep their mouth shut?

The following I sent to SABR-L in my defense:

To set the record straight: Steve Gietschier is not listed as one of the editors of the 2005 Sporting News Baseball Guide, so I would be the last to hurl charges against someone who is not even listed as an editor. (I assumed that is also the reason that Willie Runquist didn't write him, either.) The only charge that I see tossed out there was that the book was badly flawed. I assume Willie Runquist wrote to the editors listed on three occasions, and didn't get a response, and that made him feel that the editors of that TSN publication didn't give a damn. The only time I even thought of Steve in context of the 2005 Guide was after Steve wrote a defense of the Guide on SABR-L. The post by Lyle Spatz seems to suggest that I launched some sort of personal campaign against Steve Gietschier. I concur with everything that Lyle says about Steve Gietschier, but that only changes the subject. The problem remains the 2004 minor league statistics, and how, if possible, to find a way to correct them. The problem with the Record Book analogy is that it doesn't work. In a record book, if one year has a lot of errors, it can be corrected in a following edition. (The same for an encyclopedia.) The 2004 statistics will never be published again. That's the sad fact.Apparently the play-by-plays exist, Then the question is: how do we get the play-by-plays and be able to legally correct the record without getting into some sort of legal mess? Would Minor League Baseball be interested in having the 2004 record being corrected by a non-profit organization dedicated to baseball research? To turn this into some sort of blasphemy (for bringing up the flawed nature of the guide) doesn't solve the problem. I want to solve the problem. That is all I ever wanted to to. SABR is an organization dedicated to providing a "true and correct record," and that might even include the 2004 minor league season. There are a number of SABR members who do compile stats for leagues that never had been compiled. If we could get the primary sources, I know we have the people to correct the record. It will be a lot harder for SABR members 50 years down the line to correct the record. Carlos Bauer

Sunday, January 15, 2006

Hitting A Raw Nerve

I posted Willie Runquist’s note of the other day about the poor quality of the 2004 statistics published 2005 Sporting News Baseball Guide on SABR-L, the Society for American Baseball Research’s forum after a number of people complained about the guide. It drew a sharp response from Steve Gietschier, Senior Managing Editor, Research, The Sporting News. I posted the following response to Steve Gietscher’s comments.

While I understand Steve Gietschier's touchiness about the subject, I will assure him that I didn't question his or TSN's integrity, but, of course, they did publish the stats, and the question still remains as to whether they knew the stats were that flawed.

Geitschier: I can assure both Carlos Bauer and Willie Runquist that we surely do give a damn. Anyone who doubts this is invited to come to our offices any day between the end of the baseball season and the tenth of January and watch an understaffed group of editors work on our annual baseball books while simultaneously performing all the other tasks we are called upon to do. No tears, please, it's just the truth. We do the best we can in the time we have allowed, and the data we were preparing after the 2004 season were severely flawed. In my note added to the letter sent to me by Professor Runquist, I merely suggested a way to mollify irate buyers of the volume, and a way to correct obvious errors. I must say that I didn't know the extent of the errors before Professor Runquist brought the matter to my attention. I came to the matter with an open mind, and Professor Runquist's thoughts are purely his own. By publishing the note does not mean I necessarily endorse all of his feelings, any more than I believe Steve Gietschier is responsible for compiling the stats so poorly. I'm sorry, however, that Steve seems to take it so personally. But I thought readers of my blog should be apprised of the matter, and I still do. There are, however, several questions I think TSN might want to review in the wake of this matter: Did they know the extent of the matter, and if they did, does journalist ethics require a note of explanation when they published the stats? I remember years ago, the Mexican League stats were published with a note stating that they never got the final averages in time for publication, and that the stats should not be considered final. Does the buyer have no say in a flawed work?

Geitschier: Carlos suggests that TSN post corrected 2004 stats on our website, but as Greg notes, those stats don't exist. Besides, don't the individual leagues have websites? Don't they care about their own stats? The problem with the above is that the leagues don't charge $18.95 for the privilege of looking at the stats. One last point: Greg Spira says that the minor league stats were done by a different company for the 2005 Guide, but the Guide its self states on page two: "Minor League statistics provided by SportTicker." How would I, or Professor Runquist, know otherwise? Wouldn't that lead one to conclude that the problem lay with TSN rather than the longtime compiler of minor league stats SportsTicker (formerly Howe News Bureau) And if no better stats are available, that's all one has to say, and leave it at that. Sorry I touched a raw nerve. That was not my intent. Carlos Bauer

Saturday, January 14, 2006

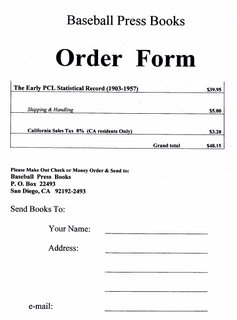

Two New Books by Willie Runquist

The 1953 edition of the famed PCL Almanac is finished, or at least as finished as it is going to get. To order a copy send $17 to Willie Runquist Box 289 , Union Bay, BC

VOR 3B0 CANADA

In addition I have revised something I wrote long ago when I had access to a real newspaper. It is called "A Heavenly Series" and consists of 137 pages describing every game played between

Willie started in a few years ago with the 1938 PCL season, and has continued, one seasons at a time, to his newest, the 1953 season. I have bought every one, and find them fascinating. Each one follows pretty much the same format. Runquist begins with a two-page pennant race summary. This is followed by series-by-series stats, and a short paragraph about each series. In the next section, Willie goes into detail on each team: Games started by position for every player, batting totals and pinch hitting. For the 15 most used position players, he breaks down their batting record by series. He basically does the same thing for pitchers. He ends each Almanac with a series of Bill Jamesian type essays. Most of the Almanacs average between 170 to 180 pages. But they are for the hard core Coastleague aficionado. I, of course, love them.

Friday, January 13, 2006

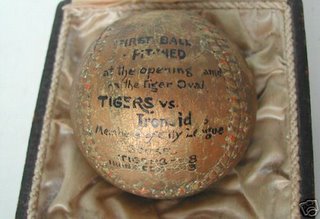

A Possibility On David Abel's Baseball

Carlos,

I have been wandering around the internet searching for some reference to "Tiger Oval". Could this have been a college park, maybe a football stadium? Football was also booming in 1910. I tried to research LSU baseball but nothing happened. If someone could determine which colleges and universities used the nickname Tigers(U. of Missouri also comes to mind) it might lead to a solution about Tiger Oval.

Karl (Knickrehm)

Thursday, January 12, 2006

A New Book on the Hollywood Stars

I just received the new issue of the Pacific Coast League Potpourri, and found the following note on the PCL Stars book. Remember that the newsletter, six-issues, cost only $15.00 a year.

And can be ordered from the PCL Historical Society, 420 Robinson Circle, Placentia, CA 92870

Wednesday, January 11, 2006

A "Read It & Weep Story" from Willie Runquist

I have come across something hat may be of interest to those interested in the minor leagues. The 2005 edition of the Sporting News Baseball Guide (containing 2004 statistics) is badly flowed in that many player's records are missing for some (or maybe even all) of the teams in the leagues above Class A.

I have neither the patience nor the inclination to review all of the teams but I have checked batting and pitching records against the fielding records of several teams in the International, Pacific Coast , Eastern and Texas leagues . Almost every team I have examined showed some corruption, missing the batting and/or pitching records of as many as 1/3 of the players listed in the fielding stats. It is not just the "less thans" as many of them could be classified as regulars. I have not made an extensive review of the teams below AA, but so far I have not discovered any omissions from the California, Midwest, Northwest, Pioneer or Arizona leagues.

I wrote three times to The Sporting News starting in late October. While the letters are not terribly articulate, I even suggested a possible solution to the dilemma caused by their carelessness. I have not received a reply— or any other indication that they even give a good damn!

I am not sure what to do next. Do you think this is important enough that SABR should pursue the issue? I would dearly love to put the matter in someone else's hands.

—Willie Runquist P.S. This is not the first time that TSN as screwed up big time. In 1999, the fielding records for the Texas League are a repeat of those from the Southern League. While no one I know really cares much about fielding data, they are the only source of information about positions played.

Note: Would those of you out there who are SABR members contact me with your ideas of how to proceed. I personally doubt that SABR, as an organization, would want to cause problems for TSN, I think it might be appropriate to broach the matter with them. As they do have a webpage, maybe they could put up corrected stats there, or at least email those stats to people who have bought the guide in the first place. Any ideas would be appreciated. From those who are not SABR members, also.

Tuesday, January 10, 2006

Monday, January 09, 2006

A Question on an Old Baseball

If anyone knows anything, or have any ideas, please contact me, and I will pass it on.

Sunday, January 08, 2006

From The Sporting News, January 13, 1900

From The Sporting News, January 13, 1900

A Profile of the First Great PCL Power Hitter, Truck

“Truck”

Note: Harry Lochhead played in 1899 for the worst team in major league history, the

Truck

Saturday, January 07, 2006

Friday, January 06, 2006

Thursday, January 05, 2006

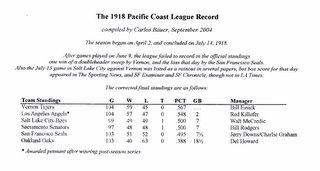

The 1918 Season Recompiled

The 1918 Season Recompiled

That brings us to 1918, the season where the Coast League threw in the towel at mid-season. In the Coast League Cyclopedia, we used the pitching records as compiled by Robert C. Hoie, of

Last year we decided to compile the batting side of the 1918 season. We felt that there was a good chance— considering that only individual batting stats made it to print— that those batting statistics had been sloppily compiled. At the same time we compiled our batting stats, we compiled pitching stats in order to see that runs and hits made by batters matched runs and hits allowed by the pitchers. We expected some minor discrepancies between our compilation and the Robert C. Hoie compilation, and a great number between our batting stats and the batting record published the following spring in the baseball guides.

Again, we couldn’t have been further off the mark! As it turned out, we found relatively few discrepancies with our compilation and that of the league statistician on the batting side of the equation. With Mr. Hoie, it was quite a different matter. In the four categories (games pitched, games started, complete games, shutouts) where it’s virtually impossible for one box score to differ from another, we found fully 20% of pitchers’ records in the league to be in error in the Hoie compilation. And, overall, we found 119 “discrepancies,” many of which we believe cannot be explained away by the use of different box scores.

To give the reader some idea of what we call “discrepancies,” we will give the details on three that we find instructive:

1) While Mr. Hoie lists Hi West with 78 strikeouts, we were only able to find 28. While a strikeout or two might be explained away by a different source newspaper, fifty seems to be somewhat beyond that type of explanation.

2) Mr. Hoie credits Jack Picus Quinn with 13 victories, yet Quinn pitched complete games in 14 contests where his team scored the most runs. And in five of those contests (on April 9, May 15, June 16, June 26, and July 9), the opponents did not score, which— according to Mr. Hoie— gave pitcher Quinn four shutouts! (Additionally, it did not apparently change the win-loss record of the pitchers he opposed. Another perplexing turn of events.) We checked every one of Quinn’s games pitched in the following papers: San Francisco Chronicle,

3) Spider Baum is one of the great PCL— and minor league— pitchers of all time. Mr. Hoie lists Baum with 7 losses. We have 8. In five of those losses, Baum was the only

While Mr. Hoie might be a fine historian— though we have found only two articles with his name on them— it appears to be nothing more than a dilettante when it comes to compiling league averages. The point being: It’s not that easy to compile averages from box scores, and— by extension— a book like this, with more than a half-million pieces of data is bound to have its share of errors, though we have made every effort to keep them to a minimum. And so we ask an reader who finds any possible error to contact us. After all, they are still making corrections to the major league record in the encyclopedias some thirty-five years after the first Macmillan Baseball Encyclopedia came out.

One additional note on 1918: In compiling our pitching averages, we came across several games where earned runs (called runs responsible for by the PCL) did not appear in any of the box scores we consulted. What we did was use the weekly pitching stats issued by the league, and published in several papers around the league every Tuesday, that gave wins, losses, and runs responsible for to determine earned runs for the few games in which they were missing. When we didn’t have the RRFs for a game, we subtracted what we had for each pitcher involved in the game from the weekly RRF totals. In no case was the pitcher involved in more than one “missing RRF game” during the week in question.

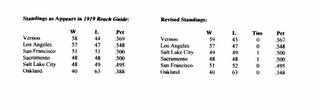

Our 1918 standings are also at variance with the official published record, as indicated below:

We believe the following will demonstrate why the published league standings are in error:

By 1918 standings were carried on a daily basis in most— if not all— the newspapers in league cities. Therefore, we immediately knew the date when the errors took place. With the standings issued after games played on Sunday, June 9, we found the one of Vernon’s two wins over Sacramento and San Francisco’s loss at Salt Lake were not counted for some reason in the four papers consulted (SF Chronicle, SF Examiner, Sacramento Bee, LA Times). After games played on July 13, the LA Times listed the

At the league meetings that winter, the 1918 season had been long forgotten, and the owners only concentrated on the coming 1919 season, and the expansion of the league to eight clubs. We found no discussion of protested games, or even about compiling pitching stats to go with the batting stats that were issued by the league on a weekly basis during the season. No pitching averages were ever issued, so we believe that was the reason those games were never picked up by the league statistician. Had the league statistician— who did such a marvelous job on the batting— finished compiling the pitching statistics, we believe the standings would have been found to be in error and corrected, especially since the official batting statistics apparently included those games.

Wednesday, January 04, 2006

1918, Part Two

The Year the PCL Threw in the Towel, Part Two

© 2004 by Carlos Bauer

Nevertheless, there were other signs that all was not well financially in the PCL. Salt Lake City, which had put a good team together, saw its attendance drop off so badly that the club instituted “twilight games,” with the first pitch at seven in the evening, in order to attract enough fans to Bonneville Park to keep the club solvent.

The Coast League was not alone in facing the very real specter of financial disaster Up in the Pacific Coast International League, Portland and Seattle appeared to be well supported by their fans, but after seeing almost nobody show up for a Saturday game in Tacoma on May 26, owner Russ Hall— a former Coast League infielder and manager, who also had a brief trial in the majors, and who went on to be one of the founders of the Association of Professions Baseball Players of America and its first Secretary— told the other owners in the league that he would not be able to continue after the scheduled Sunday doubleheader. Tacoma ownership was not to blame, as the club was in second place at the time and in a real battle for the flag.

In short order the league notified Spokane that they would be dropped to make the league a four-club circuit. The new configuration, however, only limped on through July 7, when the league gave up the ghost. The Portland franchise of Judge McCredie lost $5,000 in the endeavor, quite a large sum at the time.

While turmoil was constant off the field for the PCL, a great pennant race was taking place on the field. Through much of May, Salt Lake City remained atop of the standings, but the pennant race tightened up, with the last place San Francisco Seals only six games out of first place. The Los Angeles Angels, which held down second place for much of May, pulled into a tie with Salt Lake on June 2, after which the two teams battled one another for first place throughout the rest of that month.

The last week of June proved to be the undoing for Walt McCredie and his Salt Lake City club. On Tuesday, June 25, the Bees began a seven-game set with the Angels for first place at Washington Park in Los Angeles. Los Angeles finished the previous week with a one-game edge over the Bees.

Things started off splendidly for Salt Lake, as the team took the first contest 5-1 behind the seven-hit pitching of Tim McCabe. That pushed the Bees into first place by percentage points. Then the Angels reeled off five straight wins against Salt Lake, leaving the Bees 4½ games out, and in third place behind the Vernon Tigers.

While the five-game win streak give the impression that Los Angeles wiped the floor with the Bees, that was not the case. It was an extremely hard-fought series. Game 2 featured a pitching battle between Walt Leverenz and Paul Fittery, both mainstays in the Coast League. Through seven innings, Leverenz led by a 2 to 1 score. In the eighth, the Angels got to Leverenz for three runs, pulling out a 4-2 victory capped by Rube Ellis’ home run. The third game turned out to be the only game that was not close. Doc Crandall— a former star pitcher with the New York Giants, who would eventually win 230 games in the PCL— pitched a four-hitter, winning 7-1. Game 4 was another heartbreaker for Salt Lake, as Bill Pertica, another long-tenured Coast leaguer threw a two-hit shutout over Ed Willet who gave up the lone run of the game in the second inning. On Saturday, the two clubs battled to the end. Los Angeles moved out to a three run lead in the early going, then in the fifth, the Bees scored three runs to tie it up. With two out in the ninth, the Angels drove a man over to win. In the morning game on Sunday, Doc Crandall and Tim McCabe hooked up for what turned out to be another seesaw affair. LA jumped out to 1-0 lead, then the Bees tied it up in the third. The Angels took a 2-1 lead in the sixth, only to be tied up once again in the top of the seventh. In bottom half of that inning, LA pushed across the winning tally. That afternoon, Salt Lake City finally put it all together, taking a 7-0 lead into the bottom of the seventh. Walt Leverenz, on the mound for the Bees, pitched airtight ball up until then. He yielded five runs in the last three innings, but managed to hang on for the win. After that series, Salt Lake fell completely out of the race, winding up at .500 and in a three-way tie for third place by then end of the season.

During that same week, Vernon moved up into second, 2½ games out, by taking four out of seven from the Oaks up at Emeryville. Bill Essick’s Tigers, after a surprisingly strong start, fell back to fourth in early June, before starting a slow climb back into contention. And up in San Francisco, Jerry Downs quit as manager of the Seals on July 1, and Charley Graham replaced him with Charley Graham himself. Graham had not been satisfied with Downs as manager from the moment he took over the club. Downs, who brought the Seals home first the previous season, finally had enough of Graham looking over his shoulder, and announced his retirement from the game to go into the automobile business. His retirement lasted a week, until he signed with the Angels to become their new second baseman.

Following the Salt Lake City-Los Angeles series, Vernon and Los Angeles met for the second first place battle in a row. Both clubs shared Washington Park, though Vernon did play the occasional Sunday morning game at Vernon Park.

Vernon took the first two contests, and then split the Fourth of July doubleheader. All except the first game, decided by an 8-2 score, were hard fought one-run affairs. The game on July 5 produced another one-run game, with Vernon coming out on top 6 to 5. On Saturday, Tiger veteran Wheezer Dell pitched a shutout into the seventh inning, but then ran out of gas, losing 3-1. Vernon, however, came back strong against the Angels on Sunday morning, trouncing LA and their star pitcher, Doc Crandall, 7-1. In the afternoon game, Paul Fittery of the Angels and Roy Mitchell battled for 13 innings before Vernon pushed one across in the top of that inning, the deciding run scoring on a wild double steal.

In what turned out to be the final week of the season, Vernon traveled to Salt Lake City, and the Angels remained at home to face the Seals. Both teams took four out of seven games, and so the Angels finished the same 1½ games behind the Tigers as they had been the week before.

The demise of the league had been unforeseen even the previous week. On Tuesday, July 9, the league office adamantly squelched rumors that the league was about to fold. It became known, however, that Vernon owner Tom Darmody was lobbying other owners to reduce the rosters to fourteen players, though most clubs by then weren’t carrying the full complement of sixteen players anyway.

On Friday the July 12, Darmody called for a special league meeting in Los Angeles the next day. At that meeting, Darmody told the other owners that— financially— his club could not continue, no matter that his Tigers stood atop the league standings.

With that, the dam burst. First, the league owners confronted the fact that they would have to drop one team to maintain a balanced schedule. That meant Salt Lake City had to go, but that was completely unacceptable to owner Hardrcok Bill Lane and one or two other owners. Finally Charley Graham of the Seals stood up and told the other owners that his Seals did not want to continue. With the prospect of no San Francisco team in the league, the other owners decided it was time to throw in the sponge, and they quickly voted to suspend operations until the war ended.

The release to the press stated that the league would play all scheduled doubleheaders the following day, July 14, and then disband. The resolution made no mention of Darmody’s plight, but rather stated: “Exemption boards in the two states in which the league operates— California and Utah— ruled that the players are subject to the “work or fight” rule, and the league decided to abide by the decisions of the boards rather than appeal to higher authorities…”

Additionally, in an effort to help Tom Darmody’s out of the financial hole he found himself in, the league proposed a post-season championship series for the league pennant, rather than awarding it to the team that finished atop the standings at the close of play. The league announced that Los Angeles and Vernon would square off at Washington Park in a best-of-nine game series. Historically, the cross-town rivalry drew well, and all— especially Tom Darmondy— hoped that it would do so one more time.

After Sunday doubleheaders across the league, the regular season wound up with Vernon ahead in the standings by 1½ games at the close of action on July 14, 1918..

The final chapter of the pennant race began on Wednesday, July 17, when the Angeles and Tigers met at Washington Park in the first game of what was billed as the Championship of the Pacific Coast League. Both clubs starting lineups had remained pretty stable throughout the season, and sported only two new faces in the playoffs. Bob Meusel, on furlough from the Navy, joined the Vernon club, playing first base. He replaced Babe Borton, who only hit .265 during the season. And the aforementioned Jerry Downs, who took over second base for the Angels two weeks before the close of the regular season.

In Game One, Curly Brown faced Roy Mitchell of the Tigers. Mitchell, who had been with Vernon for four seasons, finished the 1918 season at only 7-7, but had a sterling 1. 82 ERA. The opposing pitcher, Curly Brown, had an even better 1.56 ERA, and he finished the season with 12 wins against 7 losses. The Angels jumped out to a quick 4-0 lead, and then increased that to 7-1 by the eighth inning, knocking Roy Mitchell out of the box in the process. In the top of the ninth, the Tigers attempted a comeback, but fell just short, letting the Angels escape with a 7-5 victory.

Game Two featured the two pitching stars of their respective clubs: Doc Crandall and Jack Quinn. Quinn set the all-time PCL season record in 1918 with 1.48 ERA, while Doc Crandall led the league with 16 wins. Both starters pitched complete games, Quinn giving up seven hits and three runs; Crandall one run on six hits. With that, the Angels took a 2-0 edge in the series.

On Friday, Wheezer Dell and Paul Fittery both pitched shutout ball for the first six-innings. The top of the seventh brought in the first two scores of the game, both notched by Vernon. The Tigers added two more in the eighth, while the Angels only managed one tally, making the final score 4-1, Vernon.

Saturday had another pitchers’ duel, this time between 40-year-old Charlie Chech— who began his Coast League career in 1912— and Angel veteran Paul Fittery, who had won as many as 29 games in the league, but had an off year in 1918 (11-13 2.66). Chech didn’t have much of a fastball left (attested to by his meager 24 strikeouts in 141 innings), but didn’t walk many either (18 BB), and all in all wound up the season with a 9-11 record and 2.11 ERA. The Angels tallied the first score in the sixth, adding another in the eighth, after which Bill Essick removed Chech for a pinch hitter. When the counting was done, Los Angeles had 2 runs and Vernon but 1.

Going into the Sunday doubleheader, the Angels held a 3-1 series edge over Vernon. The morning game featured Roy Mitchell, who had been knocked out of Game One, against Doc Crandall who pitched brilliantly in Game Two. This outing, however, had Mitchell come back to pitch a 2-hit shutout. Into the eight inning, Crandall had held Tigers to one run, but gave up 2 in the eighth, and Ralph Valencia replaced him on the mound in the ninth.

The afternoon contest pitted Jack Quinn against Curly Brown in another low-scoring one-run affair. The two veterans battled down to the wire, with the Angels’ Curly Brown picking up his second win of the series, mainly because he scattered the 13 hits he gave up. The 4 to 3 win left Los Angeles needing only one more win to clinch the championship.

Because there was no need for a travel day, a rare Monday game was played. Wheezer Dell and Paul Fittery hooked up for the second time in the series. Both pitchers had been wild at times that season, and both walked 7 men in the game. Wheezer Dell gave up one hit less than Fittery, but bunched too many of them together in the eighth inning, and Los Angeles brought four men across the plate. Up until that inning, the crafty veteran had pitched shutout ball. The game ended with a 4-2 victory for the Angels— giving them their second PCL Championship in three seasons—, and with that brought the curtain down on the war-shortened 1918 baseball season.

In the aftermath of the Coast League shutdown, shipyard and service baseball came into its own. In the two primary Coast League centers, Los Angeles and San Francisco, strong leagues were formed. Stocked mainly with Coastleaguers, these leagues played ball on par with any that had been played that season. In the Los Angeles area, the Southern California War Service League was formed by Angels owner John Powers, who wanted to provide an entertainment for the people of Los Angeles, and to provide some income for his Washington Park. It boasted of six teams, of which two were military teams. One team, the San Pedro Sub Base team, even boasted two future Hall-of-Famers in Bob Meusel and Harry Heillman. The defense industry teams picked up players such as Sam Crawford, Ken Penner, Red Killefer, and even future Black Sox infielder Fred McMullin. Up in the Bay Area, the San Francisco Shipbuilder’s League put on an even better class of ball on the field, attracting the Seals, Oaks and Sacramento players, plus a number of major leaguers, including Swede Risberg, Joe Gedeon and Ossie Vitt.

The San Francisco based league played every Sunday up through the Armistice on November 11, 1918, when— magically— players discovered they no long needed a draft deferments.

The Los Angeles based War Service League began as a Saturday and Sunday league, but as the demand on war industries grew, Saturday shifts changed the league into a Sunday-only affair. After games played on September 1, the league announced that it would suspend operations “for a month” because players on service teams were being deployed overseas. Supposedly the league would resurrect once new teams could be formed, and hopefully stocked with major leaguers enticed west, now that the major leagues had closed down.

The War Service League’s hopes never materialized. Shortly after suspending operations, the Los Angeles area was hard hit by the Spanish Influenza, forcing health officials to prohibit any large gatherings of people throughout that fall and winter. The pandemic killed an estimated 675,000 Americans over the fall and winter of 1918. World-wide, some 40 million lives were thought lost.

The PCL’s final championship series turned out to be well attended, and did much to solve Vernon’s financial woes. And that gave a somewhat better ending to a difficult season.

But when the league officially ceased operations “for the duration” of the war, neither fans, nor players, nor owners knew when the PCL would play their next season. Many secretly feared that the Coast League had stepped out onto the ball field for the very last time.

The following statistics were compiled after the above article was written, so there are some discrepancies, which I will deal with tomorrow, when I post my notes on compiling the 1918 Pacific Coast League season that come from the introduction to my book, The Early Pacific Coast League Statistical Record, 1903-57.

Tuesday, January 03, 2006

1918, The Year the PCL Threw in the Towel

The Year the PCL Threw in the Towel

© 2004 by Carlos Bauer

From the moment of the sinking the passenger ship Lusitania off the Irish coast in 1915, with the loss of 128 American lives, most people felt that the United States would eventually be dragged into the first World War. Nineteen sixteen was a nervous year for the republic, but the country managed to stay out of the conflict across the waters, and baseball even prospered. But in February 1917, the United States broke off relations with Germany, and in April the Congress declared war. On the home front, industry geared up for the war, and people’s minds drifted away from the national pastime. Out on the Pacific Coast, the cloud of war only began to appear after the 1917 season ended.

Going into the annual Coast League meeting in early November, President Allan T. Baum announced that there would not be any team changes for 1918. Once the two-day meeting ended, however, the league president issued the following statement: “Only the mere formalities are to be completed before the Portland Club will have been replaced by Sacramento. Portland has decided to enter the Northwest League next season.”

Portland had been a long-simmering problem, both for the California franchises, and for the Portland Beavers themselves. Portland had long maintained the season was too long, as the rainy season forced the Beavers to spend the last month of the season on the road. The expenses of that last road trip turned many profitable seasons for Portland into near break-even affairs, or even losses in some years. On the other side, the California clubs bemoaned all the money they were forced to spend on train fare, and additionally, for the two Southern California clubs, Tuesday games were lost when returning from Portland, as the train trip took two days. For the coming season, the Federal government had imposed an eight percent tax on passenger tickets and a ten percent tax on Pullman tickets. Add to that, just before Christmas, the Federal Government announced that it would be taking over all the railroads in the country for the war effort, and that left every league in the country wondering whether clubs would be permitted unrestricted use of the railway system, as they had during the 1917 season.

With the war drawing closer each day, owners wanted to retrench, and even some thought was given to cutting Salt Lake City loose from the league, making the Coast League an all California affair. What saved Salt Lake City was the fact that— since its entrance in the PCL in 1915— business leaders of that city gave subsidies for travel expenses to visiting clubs. Charter PCL member Portland never had such an arrangement, which made it much more often a candidate for being dropped from the league.

Part of the agreement with Portland owner Judge Walter W. McCredie called for the Portland club to sell its players to Sacramento, and that his nephew, Walt McCredie, long-time manager and one-time player for the Beavers, would join Sacramento as field leader. Then on December 1, Sacramento balked at the deal, citing Portland as requesting exorbitant amounts for players. But rumors circulated that the Sacramento principals had not secured all the financing to run a Coast League franchise. Charley Graham— who had been first a player-manager in the PCL, and then a part owner of the previous Sacramento franchise— put the group together, but apparently some of the partners got cold feet at the last minute. With the Sacramento franchise on shaky ground, league owners— then called magnates— began in earnest discussing the possibility of becoming a four-club circuit, Salt Lake City once again becoming the prime candidate for being dropped.

Finally, in January, a special league meeting was called for in Los Angeles to resolve all outstanding league issues for the coming season. At that meeting, Charley Graham showed up with another group of investors, and that group demonstrated that it had enough financial wherewithal to secure the Sacramento bid. Graham then became Secretary of the club. And a compromise was also worked out between Portland and Sacramento on players: Sacramento would be permitted to buy as many players as they wanted, but any player Sacramento didn’t want— or come to an agreement on price— would be offered on the open market.

Once the composition of the league had been settled upon, owners approved the traditional 30 week/30 series schedule that would run from April 2 through October 27. The league also took care of one other piece of outstanding business: For financial reasons, the league mandated sixteen-player rosters, the smallest since the early years of the league.

In the wake of the league confab, the new Sacramento franchise purchased five starters from Portland that would form the core of the new club. They also named Bill “Redmeat Bill” Rodgers, the Portland second baseman for the last six years, as playing-manager of the Senators. The very next day Walt McCredie, who had been the managerial choice of the first group of Sacramento investors, then signed to manage Salt Lake City. Presumably owner Bill “Hardrock” Lane thought that would give the Bees the inside track on any players Sacramento did not acquire. And that, in the fullness of time, is exactly what happened.

Shortly thereafter, the Vernon Tigers named its new manager, Vinegar Bill Essick, who pitched for Portland in 1905 and 1906, before being sold to Cincinnati. Owner Tom Darmody brought Essick west from Grand Rapids, where he had been manager and part-owner of the Class B Central League club for the past several seasons. Essick was about to embark on a very successful eight-year managerial career with Vernon before becoming the longtime Southern California scout for the Yankees. He picked up the moniker “Vinegar Bill” as a young pitcher who had, as one reporter wrote, “a rather sour disposition.” Vernon finished dead last in 1917, and its manager George Stovall got the boot the day the 1917 season ended.

Up in the Pacific Northwest that January, Judge Walter McCredie attended his first Northwest League meeting, where the league immediately changed its name to the Pacific Coast International League. The Pacific Coast League immediately filed a protest with the National Association, but that went nowhere with baseball’s national governing board. The Judge also announced the new nickname of his club, the “Buckaroos.” The name change was necessitated by the fact that Vancouver had used “Beavers” as their nickname since the 1916 season.

Underlying all the turmoil of the past few months was a constant rumor that two unnamed PCL franchises teetered on the brink of insolvency. Many reporters speculated that the two clubs were Vernon and, surprisingly, the San Francisco Seals.

Nothing in the Coast League is ever easy.

The run-up to training camp showed that clubs had more than the usual problems in filling roster spots, even the reduced sixteen-man ones. Any number of players had joined the service or had taken defense industry jobs, primarily in the Southern California oil industry, and/or shipyards up and down the coast. The Oakland Oaks were the worst hit club. On the eve of spring training, they only had one catcher on the roster, but he was at least last year’s starter, Dan Murray. The rest of the line up had more holes than a doughnut shop: two of their starting outfielders, Billy Lane and Hack Miller decided to remain in defense-related jobs; first baseman Rube Gardner retired shortly after the 1917 season closed; third baseman Rod Murphy joined the Marines; and starting shortstop Bill Stumpf had been drafted by the Pittsburgh Pirates. The situation in Oakland looked so bleak that owner Cal Ewing threatened to fill his ranks with sandloters.

Two clubs decided to travel east to find players. Walt McCredie mined his contacts with major league clubs to get their surplus players; and Vernon’s new man, Bill Essick, scoured the Midwest, where he hoped his contacts would yield some fruit. Another club, the Los Angeles Angels, managed to retain a group of solid veterans, and added to the mix long-time Detroit Tiger right fielder Sam Crawford, who had decided to make Southern California his permanent home. San Francisco thought they had come up with an infield and pitching staff stronger than the one that carried them to the 1917 pennant, but their outfield appeared weak.

With all six clubs scurrying off to spring training all over Southern California and the Central Valley, a bombshell exploded: Long-time Seals owner Hen Berry sold the San Francisco club to a group headed up by Charley Graham (who was still part owner and Secretary of the newly formed Sacramento franchise) and Charles H. “Doc” Strub, who had been a teammate of Graham in college. Graham, of course, resigned his position with Sacramento, and disposed of his holdings in the club, before moving to San Francisco. Graham and Strub would control the franchise until the mid-1940s.

Spring training began under showers, and the weather stayed wet throughout the month of March. As training progressed, reporters began making predictions on what clubs should be strong and what clubs would not. Los Angeles and, surprisingly, San Francisco were thought to be the two strongest clubs in the league. Oakland, obviously, and Vernon— which retained much of the same pitching staff that finished last in 1917— were figured to finish at the bottom of the standings. Most observers felt that the Salt Lake City Bees, with four solid pitchers—three of whom (Ken Penner, Walt Leverenz and Jean Debuc) had won 20 or more games in the Coast League in 1917— would be the most improved team in the league. Sacramento seemed to be just a cut below Salt Lake City, even though it, too, had came up with a good crop of pitchers, and got some solid position players from the previous year’s Portland Beavers club.

The Bees’ chances took a turn for the worse, however, just as camp was winding up: pitchers Ken Penner and Jean Debuc rolled an automobile, putting both on the sidelines for a several weeks with broken ribs.

The PCL season opened officially on Tuesday, April 2 in San Francisco, Los Angeles and Sacramento, and by week’s end lowly rated Oakland had taken five games from the previous year’s pennant winning Seals to top to the standings. In Los Angeles, Sam Crawford exploded on the scene for the Angels, getting a couple of hits, stealing a base, and throwing out two runners in his first game. After the second week, both Oakland and Vernon had surged way out in front of the pack. San Francisco’s weak outfield manifested itself in the early going. Charley Graham bought long-time star outfielder Harl Maggert (.287 lifetime minor league average to go along with 516 stolen bases), who had become expendable when that club signed Sam Crawford, from the Angels. Maggert’s knees had been going for several seasons, but Graham thought there still remained some life in the old warhorse. As soon as he joined the Seals, Maggert twisted one his knees, and was sidelined for a week or so. To add to the Seal’s frustration, Roy Crohan— whom Graham had counted on to fill the shortstop position as he had in 1917— still had not shown up.

Yet, as soon as it looked the bleakest, the Seals righted themselves, and made a run on the league leading Salt Lake City Bees. Then, as quickly as they made their surge, the club took another dive, finishing up April once again at the bottom of the heap, though by then Crohan had joined the team.

The month of April ended with Vernon slipping past the Bees for first place by a single game.

During the first week of May, Oakland was hit by the first of many player defections. The already weakened Oakland Oaks lost their starting second baseman, Eddie Mensor, to a St. Helens, Oregon team in the Columbia-Willamette Shipbuilders’ League. Mensor had been one of the bright spots on the Oaks roster, hitting a solid .278 in a season dominated by pitchers.

The same week as Mensor jumped the Oaks, rumors spread throughout the league that several Coast League umpires were attempting to recruit players for defense industry companies in and around the Bay Area.

But what was happening on the West Coast had been taking place all across the country. The Sporting News ran an editorial that same week denouncing Bethlehem Steel, which had begun recruiting players from professional baseball, including major leaguers, for its steel mill league in Pennsylvania. “It now appears,” went the Sporting News editorial, “this privately conducted organization, operated for the purpose of furnishing recreation and entertainment for steel mill workers…is invading the ranks of players [in Organized Baseball] under contract, and under various subterfuges, endeavoring to induce some of them to break their pledges and repudiate their signed agreements.” While the Sporting News only dealt with Bethlehem Steel, the editorial could just as well have been written about shipbuilders on the West Coast. Or industrial firms in the Midwest.

In the second week of May, Salt Lake City jumped back in front of the Vernon Tigers by one game. While Salt Lake City had counted on its stellar pitching staff to take the club to the top, it was its heavy hitting that carried the day, at least in the early going. Three of their players topped the .300 mark, led by Larry Chappell at .372, and two others were just a notch below the .300 mark. Their pitching was hampered by the auto accident that sidelined the two pitchers, but one of those pitchers, Jean Dubuc, came back in late May, and ran off three straight wins. Veteran Walt Leverenz, who had pitched three seasons for the St. Louis Browns, topped the staff, and the league, with 6 wins.

The deeper into May the league got, the bleaker the future looked for the PCL. First, more players were notified that they were draft eligible, then Oakland got hit by three more players defecting to shipyard teams, and finally, Provost Marshall General Crowder issued his famous “Work or Fight” order, which made it harder for clubs to even fill gaps in their rosters from the ranks of sandloters. The order affected all men between the ages of 21 and 31, but it was commonly believed that the upper age limit would soon be raised to 40 years old.

With the war in full swing, many owners felt that attendance would dry up— just as it had during the last major conflict, the Spanish-American War— but PCL attendance held up surprising well early in the season, except at Rec Park in San Francisco, where a combination of bad weather and a bad ball club drove attendance way down.

Finishing up a full slate of doubleheaders on June 2, the league standings stood as follows:

Club W L Pct GB

Salt Lake City 32 26 .552 …

Los Angeles 34 28 .548 …

Sacramento 29 27 .518 2

Vernon 29 33 .468 5

San Francisco 29 33 .468 5

Oakland 27 33 .450 6

Los Angeles had slipped past Sacramento into second place by taking six out of eight contests from them, including a doubleheader sweep on June 2.

While pitching dominated in 1918, the talk of the league during the first two months of the season was Art Griggs, Sacramento’s fine first baseman, who was tearing up the league at a .445 clip, which was more than a hundred points above the number two batter, Jack Fournier of the Angels. Griggs, who had been a college footballer, started his pro baseball career in his native Kansas in 1905. By 1909 he had worked his way up to the majors for 2½ season before finding himself once again in the high minors. He battled his way back up to Cleveland in 1912— where he .304 in 89 games— but failed to stick the following season. After two years in the Federal League, mostly riding the bench, he found his way to the Coast, where his career resurrected. A lifetime .313 hitter in the minors (and .277 in the majors), 1918 was arguably his finest season. After hitting a league leading .378 in the PCL, he joined the Detroit Tigers, where he continued his hitting prowess with a .364 average in 28 games. Once again he didn’t stick in the majors in 1919, and found himself back with Sacramento. Griggs’ career ended in 1926 in the Coast League with the Seattle Indians. He went out with a bang, bidding farewell with an impressive .346 in 89 games.

Early June dealt the Coast League another body blow, and a special meeting was called for in San Francisco on June 8. The meeting was necessitated by to the National Railroad Board having raised train in the first days of June. This was the second time that year that the National Board had raised railroad fares. But this time the Board, without prior notice, more than doubled the fares, catching the league completely by surprise. The round-trip fare per player, Los Angeles-San Francisco, went from $21.50 to $45, and the California-Salt Lake City trip jumped from $40 to over $80. The Coast League— because of distances between cities— always had been held hostage by the railroads. For that reason the circuit only scheduled one seven-games series a week, rather than two series a week of other much more compact leagues. At the June 8 meeting, the league approved a plan to cut down on travel expenses by mandating all road trips would be made by automobile, save those to and from Salt Lake City. The league determined that the automobile trip between the Bay Area and Los Angeles would “only take” from Sunday night to Monday at 8:00 pm at the latest, giving players a night’s sleep before beginning the week-long series’ on Tuesdays.

Even though the special meeting was called to come up with a plan to cut travel expenses, wild rumors of the league shutting down completely swirled around the meeting. In closing the special session, the league declared to the press that the Pacific Coast League would not shut down until all of baseball was forced to close. That put the rumors to rest for a while. But just two weeks later the Oakland Tribune quoted Oakland owner Cal Ewing as saying that the league would stop operations after games on the Fourth of July. No sooner had the words appeared in the press, than some backtracking began. Ewing stated that he had been misquoted, declaring that he only said that if General Crowder’s “work or fight order” pertained to all of baseball, then the PCL would be forced to close down with the rest of the leagues in Organized Baseball.

Part Two tomorrow…